Welcome to the first in a new series of posts in the Royal Historical Society’s ‘Writing Race’ series. To begin Series Two, Professor Bruce Buchan considers the prominence of race in Enlightenment thought, with reference to the work of the Scottish moral philosopher, Adam Ferguson (1723-1816) and the ‘Historical Chart’, attributed to Ferguson on its publication in 1780.

The relationship between early concepts of race and modern racism is a subject of current debate. While Ferguson’s interest in race, empire and history does not lead to the inevitable ascent of modern racism, his lectures and Chart did identify racial hierarchy as a material factor both in the ‘natural’ history of humanity, and in the civil history of peoples — concepts integral to western Enlightenment thought.

You can also read more about the new series of ‘Writing Race’, and view all the posts from Series One here.

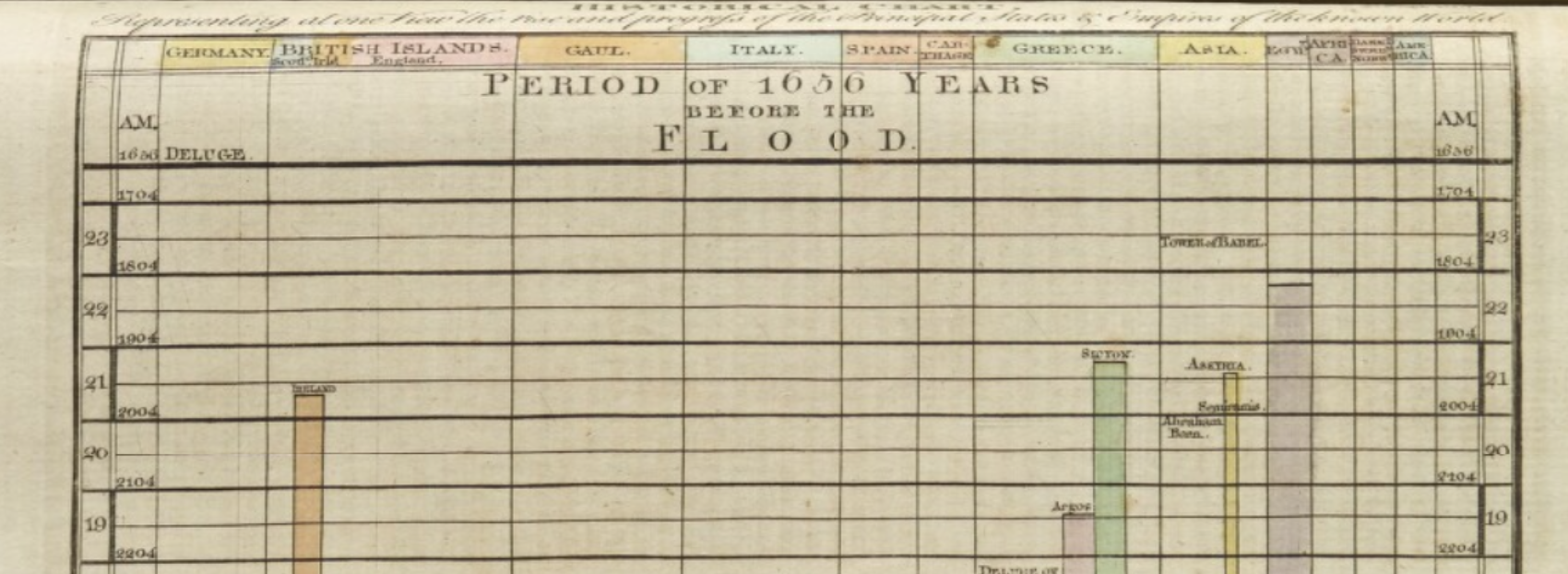

The second edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, published in Scotland between 1778 and 1784, included an “Historical Chart” purporting to show “at one view” the “rise and progress of the Principal States & Empires of the known World.” Though the Chart prominently advertised it had been “Designed by Adam Ferguson” (1723-1816) the “Professor of Moral Philosophy, in the University of Edinburgh”, there’s no definitive evidence that he was responsible for the work. Yet the mystery of the Chart’s design commends its study as a symbol of the imprint of race, empire and history in Europe’s Enlightenment.

Adam Ferguson’s ‘Historical Chart’ from The Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2nd edn, Vol. 5, 1780. National Library of Scotland License: CC BY 4.0

How are early concepts of race related to modern racism?

The prominence (or otherwise) accorded to race in European Enlightenment thought is a subject of recently renewed scholarly focus. Scholars of Atlantic history have traced the lineaments of race in the manifold mobilities of individuals and nations made possible by European empires and colonisation across the eighteenth century. Historians of the Atlantic slave trade have also argued that the practice of African slavery cemented ideas of racial hierarchy that helped legitimate the European persecution and enslavement of other peoples. The incidence of slave revolts and the rise of Abolitionist sentiment in Britain and elsewhere also drove presumptions about inherent racial differences, cementing the concept of race in Enlightenment thought. Intellectual historians have begun to explore how these ideas were taught in both moral philosophy and natural history, and where race was used as an interpretive device by colonists and ‘scientific’ travellers.

Despite this growth in scholarship on race and the Enlightenment, the relationship between early concepts of race and modern racism is a subject of continuing debate. Though it is true that concepts of race in Enlightenment discourse tended to share a certain ambiguity (in relation to matters such as definition, relevant physical or social criteria, and environmental causality), I argue here that race was entwined with the conceptualisation of historical time in Europe’s Enlightenment. This mutual inscription of race and time made the presumed hierarchical implications of human difference visible to Europeans in a variety of ways, especially, as I show here, in Adam Ferguson’s ‘Historical Chart’.

Adam Ferguson’s understanding of race

At this late stage in his career as a popular teacher of moral philosophy, and a widely read intellectual representative of Scotland’s Enlightenment, Adam Ferguson’s interest in race is representative of a broader turn in the later decades of the eighteenth century, and in Scotland in particular, toward the idea of human racial variation and hierarchy. As Scots intellectuals used the term then, race lacked biological rigidity and denoted rather that physical and cultural characteristics were malleable across time. All this can be seen in Ferguson’s use of the term, especially in his popular lectures on moral philosophy. Yet we can also detect clear evidence that he began to use the term in a hierarchical sense.

Professor Adam Ferguson, By Joshua Reynolds, 1781/82. Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh.

Ferguson occupied the chair of moral philosophy at the University of Edinburgh from 1764 till his retirement in 1785. His hand-written lecture notes covering the last 10 years of his tenure provide an invaluable insight into his thought. This has been a special study of mine for a few years now, and along with my colleague Silvia Sebastiani, we have recently published a new study of Ferguson’s presentation of race in the lectures. What his notes reveal is a record of engagement in the last years of his career with the concept of race and the fate of empire, themes to which he was also drawn in writing his three-volume History of the Progress and Termination of the Roman Republic, published in 1783. This late-career interest in race and the historical fate of empire coincided in the ‘Historical Chart’ which appeared in volume 5 of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, published in 1780.

Why we should study Adam Ferguson’s ‘Historical Chart’

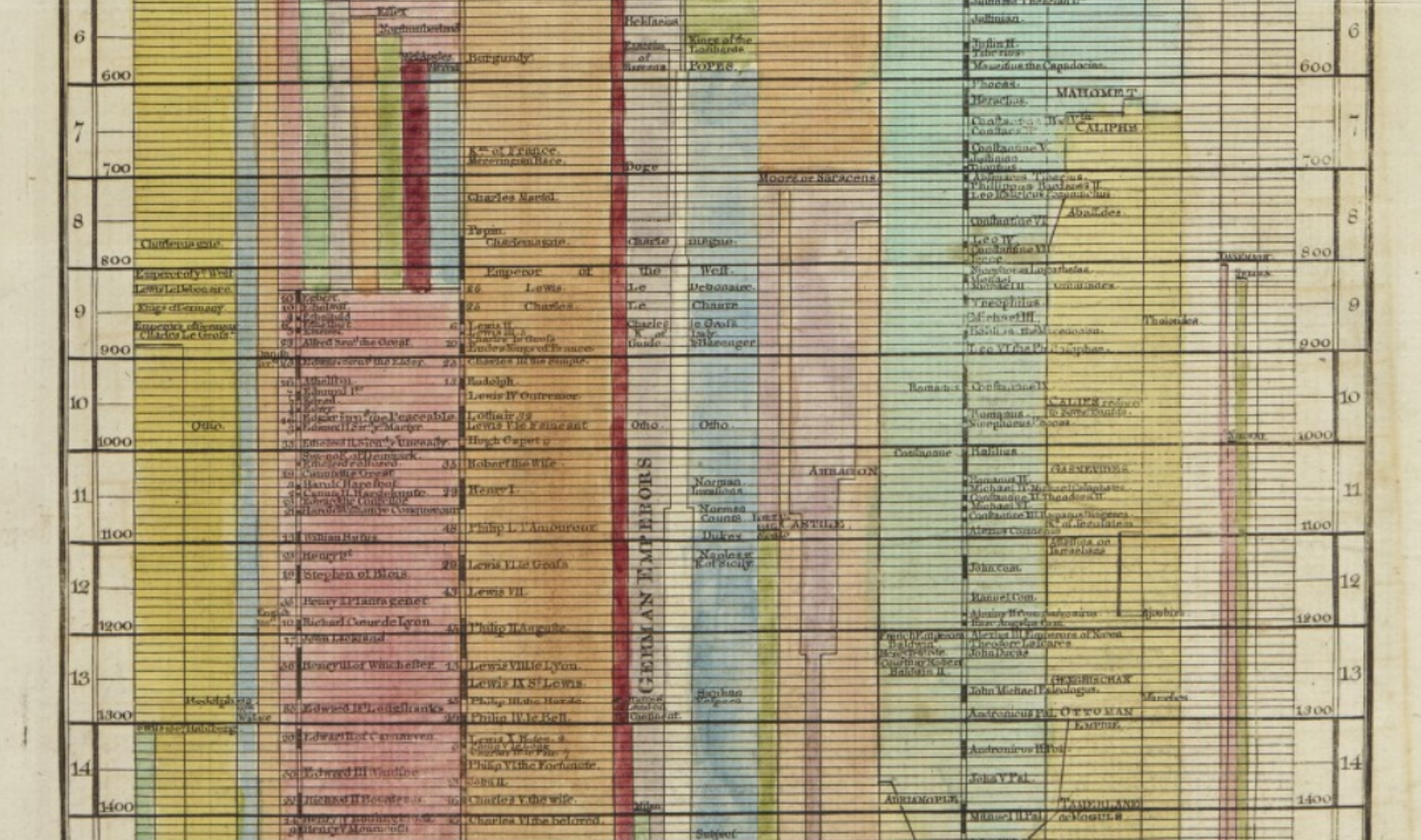

Visually, Ferguson’s ‘Chart’ looks rather conventional in its presentation of time according to an explicitly Biblical dispensation, in which the key events and figures of the past are recorded in columns corresponding to the most influential nations of Europe and beyond. Time is shown descending as a stream from the supposed Biblical flood to 1800AD. In common with other historical charts, Ferguson’s gave primary historical agency to the peoples of Europe. The division of humanity into separate columns in Ferguson’s ‘Chart’ shows some columns with a complete absence of any history, others with a marked continuity and preserved originality, while yet more are overwritten by a haphazard succession of peoples or empires, suggesting that some nations become moribund and passed out of history’s record.

Top, the head of the chart organised in columns by regions, and in rows for chronological progression. Below, world history, c.550-1400.

This variable presentation reveals the historic role that Ferguson attributed to the complicated interplay between climate and race which, he thought, so favoured the peoples of Europe and the Empire of the Romans. As he described it in his History, Rome’s Empire:

…seemed to comprehend, within itself, all the most favourable parts of the earth; at least, those parts on which the human species, whether by the effects of climate, or the qualities of the race have, in respect to ingenuity and courage, possessed a distinguished superiority.

The “principal honours” of the human species, Ferguson wrote, were only attainable in “the temperate zone” between climatic extremes. This meant that the further artistic, economic, political and social development of the races inhabiting equatorial Africa, or the far south and north of America, was severely limited – as the ‘Chart’ indicates by a complete absence of history on both continents before 1500.

World history c. 1350-1800, showing the absence of events from c.1500 in the four columns to the right of the chart, representing Greece, Asia, Egypt and Africa

How did Ferguson link race with climate?

Although he considered racial variations were “connected with Climat”, Ferguson struggled in his lectures to explain it. In a global perspective, Ferguson argued, the effects of climate were “gradual & insensible”, but “marked and striking” at the extremes. Climate was not destiny as the recent history of Europe’s global colonisation indicated. As he presented it, the ingenious advances of civilisation in knowledge and technology enabled the ‘civilised races’ of Europe to modify the worst effects of climate. The geographic range of the European race, he argued, was an artefact of imperial history which mirrored the map of the Roman Empire appearing in his History of Rome.

Map of the Roman Empire from Adam Ferguson’s The History of the Progress and Termination of the Roman Republic, Volume 1.

As Ferguson told his students:

From Scandinavia to the Senegal, from the Atlantic to the Indus. With all the Colonies that have gone out from this extensive tract. Consisting of many nations & Tongues [that] have been changed within the compass of History. [Although the]… state of nations & the seats of Empire have Changed… [and the] Fortunes of men have fluctuated… the species has appeared [here] with the greatest advantage.

Whatever its climatic and physical advantages may have been, Ferguson considered the use of reason to be a European distinction, for they are “a Race that is given to enquiry.”

When did European civilisation become ‘global’?

The implicit message of the abrupt commencement of African and American history on Ferguson’s ‘Chart’ around 1500 reinforced the global significance of European colonisation. As Scots such as Ferguson presented it, this was the universal turning point or watershed at which the parochial history of Europe became genuinely world history. Empire, conquest, and colonisation were the media of global integration given priority in the ‘Chart’, which also manifested the global ascendancy of peoples Ferguson would describe in his lectures as “the European race”.

Ferguson explicitly prioritised race in resting the entire construction of his ‘Chart’ so heavily on a Biblical temporal dispensation, and by highlighting the agency of so many of the Christian nations of Europe. Yet in Ferguson’s hands, race transcended revealed religion and became an integral element in the natural and human history of the species. The biological bonds of lineage were the bedrock for Ferguson’s conceptualisation of the full sweep of human history. There had never been a point in humanity’s past, Ferguson lectured his students, at which human beings did not live in some kind of collective, either “Clan, Race or Family”, each based on kinship and familial descent.

Conclusion: Race and Ferguson’s ‘Historical Chart’

Although Ferguson’s interest in race, empire and history did not lead to the inevitable ascent of modern racism, it did cement racial hierarchy as a material factor in the ‘natural’ history of humanity and the civil history of peoples and nations across the globe in Enlightenment thought. For Ferguson, the anatomical markers of race coincided with the geographic distributions among nations, and with the historical borders separating peoples into varying degrees of “savagery” or “barbarism”, beyond which they could not easily progress.

This was the crucial implication of his ‘Historical Chart’: that the natural history of humanity and the progress of civilisation led ineluctably to the European watershed in 1500, after which history became global thanks to the empires and colonisation that Ferguson and many other Britons and Europeans came to believe, had secured the ascent of the ‘European race’.

About the Author

Bruce Buchan is a Professor in the School of Humanities, Languages, and Social Sciences at Griffith University, Australia. His research explores intersections between colonisation and the history of ideas.

Bruce’s publications include The Empire of Political Thought: Indigenous Australians and the Language of Colonial Government (2008), An Intellectual History of Political Corruption (with Lisa Hill, 2014), and the co-edited volumes Sound, Space and Civility in the British World, 1700-1850 (2019), and Piracy in World History (2021).

Further Reading

- Bruce Buchan and Silvia Sebastiani, ‘“No Distinction, Black or Fair”: The Natural History of Race in Adam Ferguson’s Lectures in Moral Philosophy’, Journal of the History of Ideas, 82/2 (2021), 207-29.

- Bruce Buchan and Linda Andersson Burnett, ‘Knowing Savagery: Australia and the Anatomy of Race’, History of the Human Sciences, 32/4 (2019), 115-34.

- Snait Gissis, ‘Visualising “Race” in the Eighteenth Century’. Historical Studies in the Natural Sciences, 41/1 (2011), 41-103.

- Nicholas Hudson, ‘From “Nation” to “Race”: The Origin of Racial Classification in Eighteenth-Century Thought’, Eighteenth-Century Studies, 29 (1996), 247–64.

- Jean-Frédéric Schaub and Silvia Sebastiani, Race et histoire dans les sociétés occidentales (xve -xviiie siècle), (Albin Michel, 2021).

- Silvia Sebastiani, The Scottish Enlightenment: Race, Gender, and the Limits of Progress (Palgrave, 2013).

- Suman Seth, Difference and Disease: Medicine, Race and the Eighteenth-Century British Empire (Cambridge UP, 2018).

- Devin J. Vartija, The Colour of Equality: Race and Common Humanity in Enlightenment Thought (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021).

- Roxann Wheeler, The Complexion of Race. Categories of Difference in Eighteenth-Century British Culture (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000).

This research is supported by a grant from the Swedish Research Council won with Linda Andersson Burnett, entitled: ‘Collecting Humanity: Prehistory, Race and Instructions for Scientific Travel, c. 1750-1850’ (grant number: 019-03358).