In this post Helen Newsome-Chandler introduces her new volume in the Royal Historical Society’s Camden Series, The Holograph Letters of Margaret Tudor, Queen of Scots (1489-1541), published in August 2025.

This volume presents the surviving holograph correspondence of Margaret Tudor, Queen of Scots as a stand-alone edition for the first time. The 111 holograph letters (written in Margaret’s own hand) and 4 ‘hybrid’ letters (written by a scribe, with a postscript or subsection by Margaret herself) form an unprecedented epistolary archive, featuring the largest collection of holograph correspondence written in English or Scots of any medieval or early modern queen.

The letters chart Margaret’s life as a late medieval queen, including the challenges she faced in negotiating her dual identity as queen of Scots and an English princess, and her important role in Anglo-Scots politics and diplomacy in the early sixteenth century.

To mark publication of this important volume, the Introduction and full text of The Holograph Letters of Margaret Tudor, Queen of Scots (1489-1541) are now available, free to read, via Cambridge University Press, until [add date].

Born on 28 November 1489, Margaret Tudor was the eldest daughter of Henry VII and Elizabeth of York, king and queen of England.

On 8 August 1503, Margaret married James IV, king of Scots, at Holyrood Palace, Edinburgh, as part of the Treaty of Perpetual Peace – a treaty which served to secure peace between England and Scotland after centuries of hostility and warfare.

This union ‘was one of the most important diplomatic alliances made during Henry VII’s reign, and it is through this marriage that the kingdoms of England and Scotland were eventually united in Margaret’s great grandchild, James VI of Scotland and I of England. However, despite playing such a pivotal role in the establishment of the Tudor dynasty and in European politics and diplomacy in the early sixteenth century, Margaret has received substantially less scholarly and public attention than her kin.’[1]

Margaret, is, however, deserving of attention in her own right.

Margaret Tudor was a prolific letter-writer: 247 letters and diplomatic memorials (also known as ‘articles’ or ‘instructions’) written in her name survive today.

This substantial archive has not gone unnoticed. Muriel St Clare Byrne, in the introduction to her edition of the Lisle Letters (1981), noted that ‘[t]he amount of correspondence with which Queen Margaret of Scotland bombarded her brother […] and all the important persons who had to be cajoled or bullied into doing what she wanted, has to be examined to be believed.’ [2] In spite of this, there has never been a standalone edition of Margaret Tudor’s correspondence before the present volume, published this month in the Royal Historical Society’s Camden Series.

Due to restrictions of space, it has not been possible to include all of Margaret Tudor’s surviving letters in my new edition. My Camden volume therefore presents a subset of Margaret’s letters and focuses on the most exceptional part of her epistolary archive: 111 surviving holograph letters (written in Margaret’s own hand) and 4 hybrid letters (letters written by a scribe which feature a subsection or postscript written in Margaret’s hand), written in English and Scots.

The unprecedented archive presented in this edition has the potential to provide new understanding of the communicative practices, education, and political and diplomatic activities for medieval and early modern queens for whom we have few, or no surviving letters.

These 111 holograph letters form the largest collection of holograph correspondence written in English or Scots of any medieval or early modern queen hitherto discovered. In contrast, only 10 holograph letters (written in English) survive for Margaret’s younger sister, Mary Tudor Brandon, queen of France (later duchess of Suffolk). The unprecedented archive presented in this edition therefore has the potential not only to shed new light on the life, character, and voice of Margaret Tudor, but to provide new understanding of the communicative practices, education, and political and diplomatic activities for medieval and early modern queens for whom we have few, or no surviving letters.

Margaret’s holograph and hybrid letters are written across a 38-year period and document much of her life as queen of Scots. The first surviving letter was sent to Margaret’s father, Henry VII, shortly after her marriage to James IV at Holyrood Palace, Edinburgh, in August 1503. Margaret’s final letter was sent to her brother, Henry VIII, king of England, in March 1541, some five months before she died of a suspected stroke at Methven Castle on 18 October 1541.

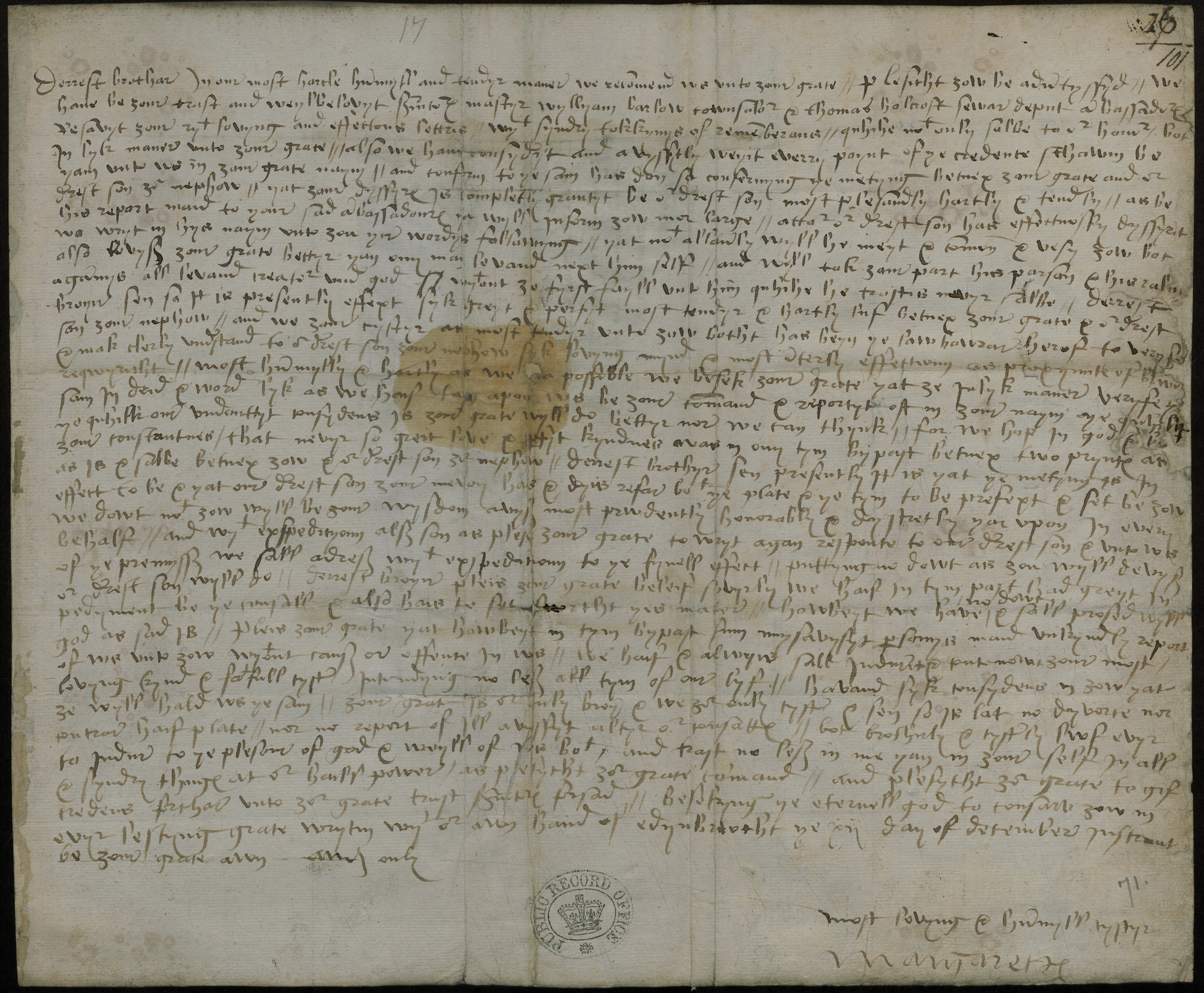

Margaret Tudor’s holograph letter to Henry VIII, 12 December 1534 (TNA, SP 49/4 fo. 70r). By permission of The National Archives.

Margaret Tudor’s surviving letters provide a fascinating insight into the day-to-day challenges that she faced as queen of Scots, especially following the death of her first husband, James IV, who was killed by Henry VIII’s army at the Battle of Flodden on 9 September 1513. For example, Margaret often wrote to Henry VIII complaining that she was facing financial difficulties and was forced to live like ‘a powr Ientyl vhoman’ (poor gentlewoman), because she struggled to receive regular payment of the rents of her dower lands. Margaret also frequently commented in her letters that she was greatly ‘mystrustyd’ (mistrusted) by the lords of Scotland, who often suspected that Margaret’s allegiances lay with England, and that she was actively conspiring against Scotland’s interest (which, on occasion, she did).

Margaret also regularly wrote to Henry VIII and his noblemen to protest of the mistreatment she received from her second and third husbands, Archibald Douglas, sixth earl of Angus, and Henry Stewart, first Lord Methven, who regularly stole the rents from her dower lands.

For example, in February 1537, Margaret wrote to Henry VIII, noting that Lord Methven had ‘spendyd my landes and profetes a pon hys avne kyn and fryndes In sych sort that he hath made them ope and pwt me In to gret dettes vysche vylbe to the sowm of viijm markes scotyes mony’ (spent my lands and profits upon his own kin and friends in such sort that he hath made them up and put me into great debts which will be to the sum of 8000 marks Scots money).

Margaret’s letters also evidence her own political ambitions.

However, the letters also highlight the important role that Margaret Tudor played in Anglo-Scots diplomacy in the early sixteenth century. Margaret was frequently called upon by John Stewart, second duke of Albany (who governed Scotland on behalf of Margaret’s young son, James V, king of Scots) to write to Henry VIII and his noblemen to seek a renewal of Anglo-Scots peace.

In a letter sent to Henry VIII on 9 December 1521, for example, Margaret requested that: ‘ȝe vol for my sake and request and for the viel of the kyng my son your nefew that the pees betwxt your sayd rawlme and thys may be prolongyd vhol saynt Ions day at mydsomar or forthar at your plesur’ (ye will for my sake and request for the wellbeing of the king my son your nephew that the peace betwixt your said realm and this may be prolonged while Saint John’s Day at Midsummer or further at your pleasure). In 1534, Margaret even wrote on behalf of her then adult son, James V, to organise a diplomatic meeting between James V, and his uncle, Henry VIII.

Margaret’s letters also evidence her own political ambitions. Following the death of James IV at the Battle of Flodden in September 1513, Margaret became the regent of Scotland, and was responsible for ruling Scotland on behalf of her young son, James V (who at the time of his father’s death was only 17 months old). This move situated Margaret in an unusual position of power for a late medieval queen, but it was contingent upon her remaining a widow. When Margaret married Archibald Douglas, sixth earl of Angus, in secret in August 1514, she was forced to relinquish the regency to John Stewart, second duke of Albany.

However, for the next 12 years, Margaret actively sought to regain the regency and the power and status that she had previously held. For example, in September 1517, she wrote to the border warden Thomas Dacre, second Baron Dacre of Gilsland, articulating her desires to ‘haue all the rwlle’ (have all the rule) and reassume her control of the regency and Scottish government. Margaret briefly regained some control of the Scottish government when she had her son declared of age to rule independently in August 1524, but she swiftly lost this power when her second husband, Archibald Douglas, sixth earl of Angus returned to Scotland after being exiled in France.

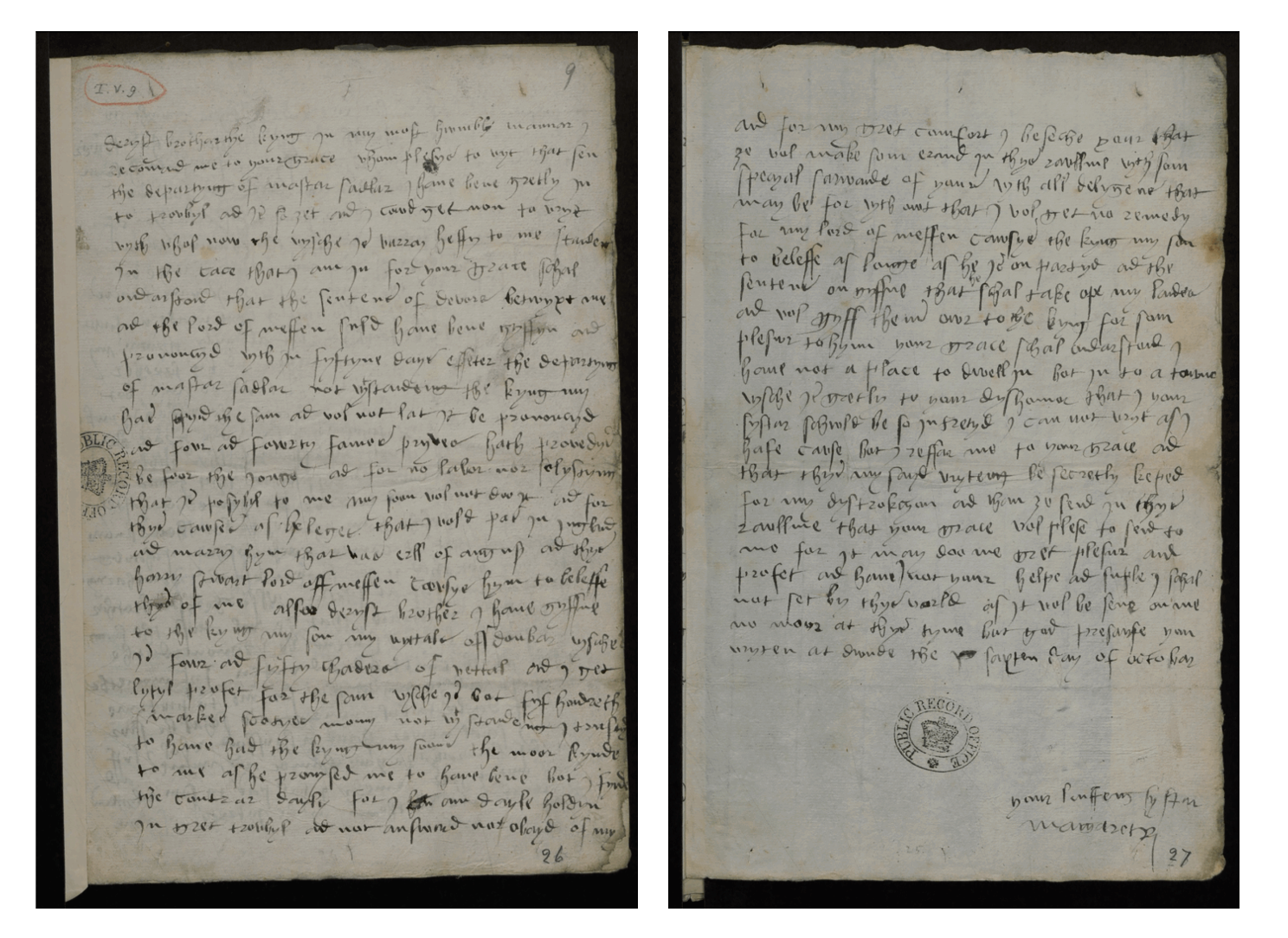

One of the most distinctive aspects of Margaret Tudor’s holograph letters is their unusual linguistic composition. To date, research into the anglicisation of Scots in the late medieval and early modern periods has shown that Scottish writers regularly adopted features of English into their writing. There is, however, ‘significantly less documentary evidence of English writers adopting Scots linguistic forms into their writing in these periods’.[3] Margaret Tudor is the only writer identified by A. J. Aitken in his study of the pioneers of Scots to exhibit such a pattern.[4] Margaret Tudor’s letters are thus somewhat unique because she incorporates the use of Scots linguistic features into her writing at certain points in her life.

The decision to standardise Margaret’s language in line with modern practices would in effect bleach Margaret’s epistolary voice, removing any opportunity to study her unique linguistic practices.

The language of Margaret’s letters may pose some challenges to modern readers, as they are presented semi-diplomatically in the edition, preserving the original spelling, punctuation, deletions, and insertions used in the original manuscripts.

However, the decision to standardise Margaret’s language in line with modern practices would in effect bleach Margaret’s epistolary voice, removing any opportunity to study her unique linguistic practices and the role that Scots and English played in her dual identity as queen of Scots and princess of England. In an effort to overcome these challenges, the Introduction of the Camden edition includes a discussion of Margaret’s use of Scots and particularly challenging terms are glossed in the main transcriptions. In addition, the appendix includes a glossary of key terms and an introduction to the Scots language and historical varieties of English.

The edition also provides a substantial introduction which explores the archive of Margaret Tudor’s correspondence, including a discussion of what letters have not survived and the value that Margaret Tudor herself placed in holograph writing. This is followed by a discussion of the language of Margaret Tudor’s holograph correspondence, as well as an analysis of the materiality and delivery of her letters. The volume also includes a detailed biography, to enable readers to better understand the complex political and cultural context in which Margaret’s letters were originally written.

Finally, the edition concludes with a handlist of Margaret’s remaining extant correspondence (appendix 3), which includes scribal letters, copies of original letters, and foreign language letters. This is the first time such a handlist has been published, and I hope that it will enable readers to access the rest of Margaret Tudor’s correspondence that is not included in the volume.

Working on this edition of Margaret Tudor’s holograph and hybrid letters has been both the largest challenge I have ever encountered, but also a delight. I have loved reading and interpreting Margaret’s unusual language and getting to know the tenacious and unyielding character that comes through in her writing. I hope that readers enjoy Margaret Tudor’s letters as much as I have.

[1] Helen Newsome, ‘“[An] old battle constantly re-fought”: Why language matters when editing early modern women’s letters: A case study of the holograph letters of Margaret Tudor, queen of Scots’, Women’s Writing, 30.4 (2023): 337-352, 339 <https://doi.org/10.1080/09699082.2023.2266040> [accessed 24 June 2025].

[2] Muriel St Clare Byrne, The Lisle Letters, 6 vols (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981) I, 65.

[3] Helen Newsome, ‘“[An] old battle constantly re-fought”, 341.

[4] Adam Jack Aitken, “The Pioneers of Anglicised Speech in Scotland: A Second Look”, Scottish Language, 16 (1997): 1–36, 28.

About the author

Helen Newsome-Chandler is a historical linguist, with expertise in late medieval and early modern women’s writing and epistolary culture.

She has received grants and fellowships from the Arts and Humanities Research Council, the British Academy, the Marie-Skłodowska Curie Actions fund, and the Society for Renaissance Studies. Her recent publications include contributions to Women’s Writing, Renaissance Studies, Royal Studies Journal, and The Edinburgh History of the Book in Scotland, vol. I: Medieval to 1707.

About this latest volume in the Camden Series

The Holograph Letters of Margaret Tudor, Queen of Scots (1489-1541), edited by Helen Newsome-Chandler, is now available online and in print from Cambridge University Press.

Fellows and Members of the Society may also order a print copy of the volume at the discounted prize of £16 per volume. To order a copy of the volume, please email administration@royalhistsoc.org, marking your email ‘Camden’.

The Society publishes new volumes in the Camden Series each year. Two further volumes will appear in 2025: The Papers of Admiral George Grey, edited by Michael Taylor (June 2025) and A Collector Collected: The Journals of William Upcott, 1803-1823, edited by Mark Philp, Aysuda Aykan and Curtis Leung (November 2025).

About the Camden Series

The Royal Historical Society’s Camden Series is one of the most prestigious and important collections of primary source material relating to British History, including the British empire and Britons’ influence overseas.

The Society (and its predecessor, the Camden Society) has since 1838 published scholarly editions of sources — making important, previously unpublished, texts available to researchers. Each volume is edited by a specialist historian who provides an expert introduction and commentary.

Today the Society publishes two new Camden volumes each year in association with Cambridge University Press. The complete Camden Series now comprises over 380 volumes of primary source material, ranging from the early medieval to late-twentieth century Britain.

HEADER IMAGE: An Engagement Portrait, traditionally identified as of Margaret Tudor, the Regent Albany and a man in royal livery. Oil on canvas. 84cm x 117 cm. Courtesy of the Bute Collection at Mount Stuart, detail/