Colin Jones, author of The Smile Revolution in eighteenth-century Paris (Oxford University Press, 2014) and former President of the Royal Historical Society considers the long history of smiling, and asks what the future might hold for this most expressive of gestures if it’s hidden behind a mask.

What happens to the smile behind the Coronavirus mask?

As a historian of the smile, the question has been preoccupying me of late. In my book, The Smile Revolution in Eighteenth-Century Paris, I traced the emergence of the modern smile – the benign, open-mouthed, teeth-revealing gesture with which we are all familiar.

Smiling became the go-to gesture of Enlightenment sociability. It broke social conventions going back to Antiquity, and reinforced in the Renaissance, that frowned severely on the opening of the lips in a smile on the grounds of social decorum, class prejudice and aesthetic appeal. By the end of the eighteenth century, the emergence of preventive dentistry and fashionable codes of sensibility stimulated a new kind of smile. This prized the facial revelation of sincere emotion transcending artificial social conventions. Witness Madame Vigée Le Brun’s 1787 self-portrait which appears on the cover of my book. It can claim to be the first modern smile in western art.

That smile found it difficult to resist a nineteenth-century return to stricter facial controls and the prizing of dignity: facial immobility made a Victorian come-back at the expense of expressivity. From the early twentieth century, however, better dentistry, plus snap photography, new cultural models (especially coming out of Hollywood) and pervasive forms of image transmission (notably through visual advertising) were laying the foundations for the triumph of the toothy, western smile.

Trying to predict the future of the smile – folly, I know: I am a historian – I suggested at the end of my book that the hegemony of the smile looked likely to remain in place and become increasingly consolidated. Although there were some developments that resisted the trend – the wearing of the face veil was the most prominent – this smile seemed to be on a path towards global domination.

And then came Covid-19.

A Masked Smile

What kind of smile regime will emerge from the generalisation of the mouth-covering mask under Covid conditions? How are we going to cope with not having the smile perform all the everyday social functions in public that it now does for us: expressing our feelings, encouraging our sociability, revealing our identities, connecting us as humans, making us feel better about the world and indeed about ourselves?

Laughing and Crying Face emojis – the two most frequently used emojis on Twitter in April 2020.

I predict two significant developments to look out for. The first is the recourse to virtual or surrogate forms of smiling – most obviously in electronic communication through the use of emojis. The most frequently used emoji throughout the world in April 2020 shows tooth-revealing smiling with tears of joy. The Runner-up, incidentally, is another open-mouthed, this time crying, face, an understandable icon of the present age.

Yet the emoji offers little for most inter-personal communication in public. What then? My second prediction is that the disappearance of the smile will be replaced by a greater emphasis on expressions around the eyes.

Back to the Mirrors of the Soul

In a way, a return to the eyes will be a return to the Ancien Régime of the smile. Before the gesture became the west’s prime facial means of expressing identity, the idea that the eyes were ‘the mirror of the soul’ had passed from ancient physiognomic lore into an everyday conviction.

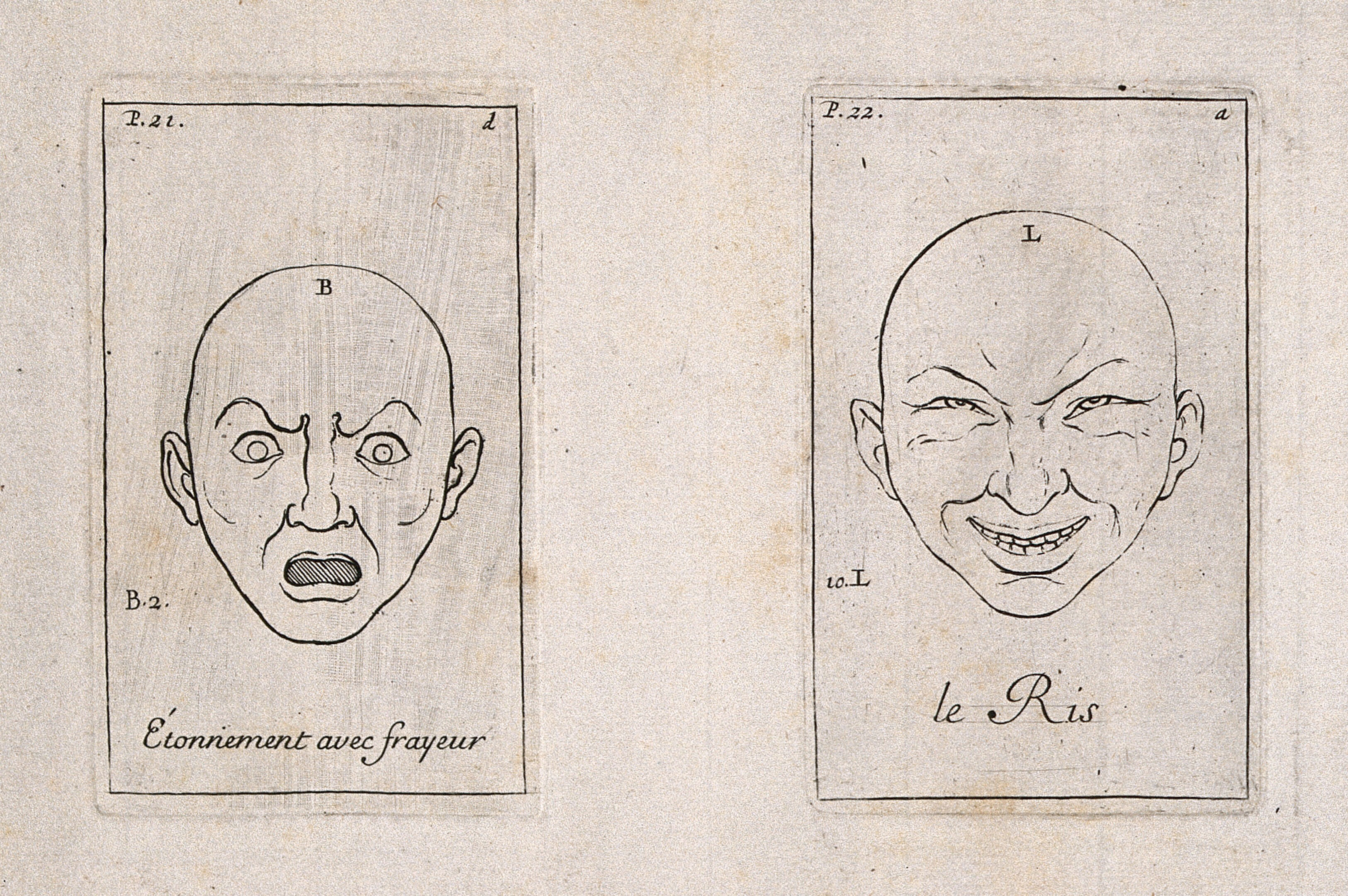

Two outlines of faces showing astonishment and fear (left) and laughter (right). Etching by B. Picart, 1713, after C. Le Brun. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Louis XIV’s Premier Painter Charles Le Brun in the seventeenth century gave it scientific endorsement, moreover. The eyes were a central feature of the famous code he devised showing the expression of the emotion in painting. While distilling knowedge of western representational traditions, it was also in line with then-current physiology: for Le Brun followed Descartes in believing that the soul was physically located in the pineal gland behind the bridge of the nose. This meant that the more the soul was disturbed by the passions the more extreme facial distortions would become, sending ripples around the face from this focal point at the centre of the eyebrows.

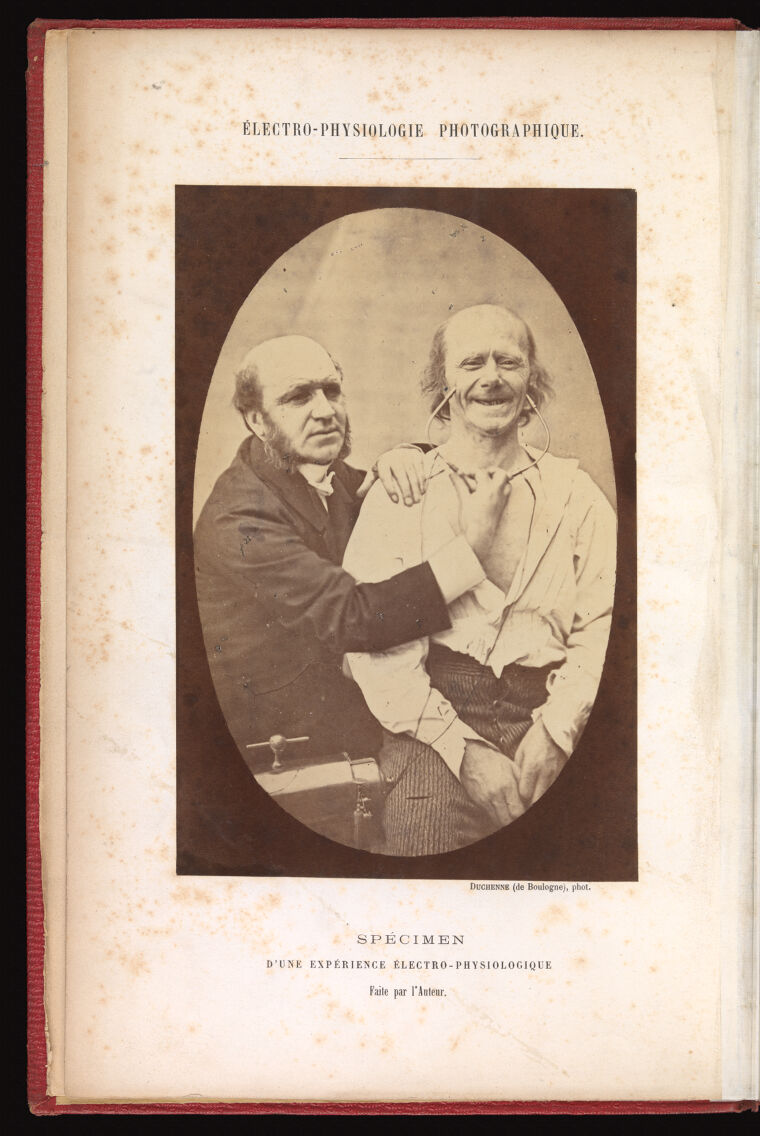

Photograph of a face being stimulated by electricity. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Le Brun could not predict the emergence of the modern smile in the following century, and we can safely discard his belief in the material existence of the soul. But his calibration of expression on the face is not a bad guide to understanding emotional reactions. Its utility as regards the smile was moreover confirmed by the work of the nineteenth-century French physiologist Duchenne de Boulogne whose experiments with electrical stimuli irrefutably demonstrated the role of the eyes in smiling.

Today, most people do not view a smile as genuine and sincere unless there is accompanying movement in the orbicularis ocuili muscles around the eyes. What cognoscenti call the ‘Duchenne smile’ is precisely our eye-crinkling, tooth-revealing western smile. It offers a vital clue to the presence of a smile even when the mouth is invisible.

In the Age of Coronavirus, one can conclude, when it comes to smiling, the eyes will have it.

Colin Jones is Professor of History at Queen Mary, University pf London. A specialist in French history, he is the author of books including Madame de Pompadour: Images of a Mistress (2002), Paris. Biography of a City (2004), The Great Nation: France, 1715-99 (2002) and The Smile Revolution in 18th Century Paris (2014). He is currently Principal Investigator on an AHRC Research Grant on ‘The Duchesse d’Elbeuf’s Letters to a Friend, 1788-94’ and Fellow at the Institut d’études avancées in Paris.